God's

Graffiti

By

Stephen Terry

Daniel,

John, and the Church, Chapter 5

(Based

on Daniel 5)

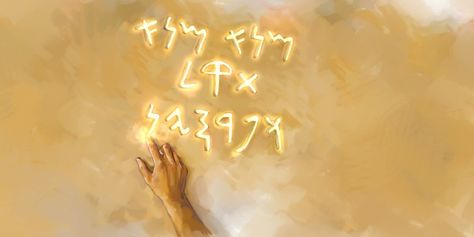

"Suddenly

the fingers of a human hand appeared and wrote on the plaster of the wall, near

the lampstand in the royal palace. The king watched the hand as it wrote. His

face turned pale and he was so frightened that his legs became weak and his

knees were knocking." Daniel 5:5-6, NIV

"Suddenly

the fingers of a human hand appeared and wrote on the plaster of the wall, near

the lampstand in the royal palace. The king watched the hand as it wrote. His

face turned pale and he was so frightened that his legs became weak and his

knees were knocking." Daniel 5:5-6, NIV

Approximately twenty-three years have passed since the

reign of Nebuchadnezzar had come an end in 562 BCE.[i] Babylon has had a

succession of brief rulers, Amel-Marduk, Neriglissar, and Labashi-Marduk, followed

by Nabonidus. While his involvement and the circumstances of his elevation are

not clear, Nabonidus became king shortly after Labashi-Marduk, a child king,

was assassinated. He departed for military campaigns in Anatolia, leaving his

son, Belshazzar, in charge. Perhaps because he had confidence in his son's

judgment, he delayed his return for ten years from 553-543 BCE, staying at Tayma

Oasis in Arabia. He also may not have felt comfortable in Babylon as he

worshipped and elevated the moon god, Sin in the Babylonian pantheon, while the

priests of the city maintained that Marduk was the supreme deity. Whatever the

reason, any concerns were set aside upon learning of invasion from the North. He

gathered his forces and engaged with Cyrus the Great, who was leading a Persian

force against the Babylonians. He met Cyrus's army at Opis on the eastern side

of the Tigris River. Suffering defeat in that encounter, Nabonidus withdrew

toward the Euphrates, perhaps expecting the Persians to follow. However, Cyrus

had a better idea. Instead, his forces followed the Tigris to the gates of

Babylon and laid siege to the city. We know of no efforts on the part of

Nabonidus to lift that siege. Perhaps he, like Belshazzar, felt that the walls

could not be breached.

We are told that, far from being fearful of the army

outside his gates, Belshazzar threw a party in the palace where wine flowed

freely and judgment was impaired. He may have pointed out to his nobles that

the gods of Babylon had preserved them thus far and would continue to do so. He

and his nobles praised and toasted those gods. Then he may have thought to

reinforce the perception of the power of the Babylonian gods by recalling a victory

from the past, the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BCE.

Calling for the vessels looted from the Jerusalem Temple. When they were

brought out, he encouraged everyone to drink from those vessels in praise of

the more powerful Babylonian deities. At this provocation, we are told that God

could no longer remain silent.

A disembodied hand suddenly appears and begins writing

on the wall. The message being written was to be seen by everyone, being written

close to one of the lampstands in the hall and therefore not hidden in the

shadows. The writing was in Aramaic, which had become the common tongue of the

Jews, evolving from Hebrew. We are told that Belshazzar shook with fear,

perhaps in part at the sight of the disembodied hand, and perhaps also because

he was unable to read the message it gave. At the presence of such an

apparition, the hall may have became deathly quiet as the revelers ceased their

carousing to watch. Then the silence would have ended as they attempted to

discern the meaning. However, no one present could do so. Belshazzar then sent

for Babylonian scholars to accomplish the task. The Bible refers to them as

"enchanters, astrologers, and diviners." These were similar to the

"wise men" that would later travel to Israel after determining that

the birth of the Messiah had taken place. Because of their education, they may

have been able to read the Aramaic writing, but were at a loss to interpret it,

even though Belshazzar had promised to make the one who could, third ruler in

the kingdom after himself and Nabonidus. Their failure only increased the

king's fear.

The queen, perhaps the wife of Nabonidus, hearing the

commotion came into the hall and reminded Belshazzar of Daniel, who had

interpreted dreams for Nebuchadnezzar and that he was still available to

assist. Belshazzar ordered him brought to the hall. Ironically, Daniel's

Babylonian name, Belteshazzar, meant the same as Belshazzar's, "Bel

protect the king." Yet Daniel was about to reveal the loss and fall of the

kingdom of Babylon. Not knowing what to expect, the prince reminded Daniel of

the reward of being made third ruler in the kingdom. Daniel, who perhaps knew

there would soon be no kingdom to rule, demurred. Looking around and seeing the

articles from the Temple in the hands of Belshazzar and his drunken court, he

was not pleased. With the spirit of so many prophets before him, he stood

before the profligate king and reminded him of the events recorded in Daniel,

chapter 4, pointing out that he knew what had happened and ignored it. Perhaps

his father's elevation of the moon god over the existing gods of Babylon caused

him to feel he had liberty to demote all gods under Sin. Whatever Belshazzar's

reasons, Daniel was having none of it.

He explained this was the reason the hand had appeared.

Then he translated the writing and gave the interpretation. The word

"Mene," repeated twice for emphasis, and meaning "numbered,"

meant essentially the same as in modern English when we say "Your number

is up." His reign had come to an end. The word, "Tekel,"

revealed that Belshazzar did not have the weight required for his position. He

had replaced the humility of Nebuchadnezzar with arrogance in ruling the

empire. That arrogance had now extended even to his treatment of the God

Nebuchadnezzar honored. Therefore his reign was to end. The final word Daniel

interpreted, "Parsin," had a double meaning. It meant that the

kingdom would be divided, perhaps more accurately torn from him by a power greater

than his own, and in a word play on those besieging the city. The word also

means Persia. The dividing then could be seen as being ordered by God but

accomplished by the Persian "dividers." In spite of the adverse

interpretation, Belshazzar made good on his promise to make Daniel third ruler

in the kingdom. But the Bible tells us that he did not outlive Daniel but lost

his life that same night.

How the fall of Babylon occurred is not entirely clear.

An account by Herodotus states that a spy entered the city and was then able to

open the gates for the Persians. Another account says that the citizens

themselves opened the gates, tired of Belshazzar's rule and his insults to

Marduk. According to Herodotus,[ii] who never visited Babylon

and was writing about it a century later, the Persians diverted the Euphrates

and accessed the city through the river gates. This is the account that

apparently Uriah Smith refers to in his book, "Daniel and the

Revelation."[iii]

Nonetheless, the Bible says nothing about the Persians diverting the river and

making an aggressive attack to conquer the city. Instead, Isaiah says that God

will open the gates for Cyrus,[iv] but does not elaborate as

to how. But this account seems to agree with those that say the citizens

welcomed him and opened the gates. The "Cyrus Cylinder," an ancient

cuneiform tablet that records the conquest of Babylon states that the city was

taken "without fighting or battle." While apparently Belshazzar died

in battle commanding forces against the Persians, Nabonidus capitulated and was

treated well by the Persians, although exiled. The golden head of Daniel,

chapter 2, had reached its end with the defeat of Babylon and now began the

chest and arms of silver as the Persian Empire rose to power.

This Article is provided

by Still Waters Ministry

Scripture marked (NIV) taken from the Holy

Bible, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica,

Inc. All rights reserved worldwide. Used by permission. NEW INTERNATIONAL

VERSION and NIV are registered trademarks of Biblica, Inc. Use of either

trademark for the offering of goods or services requires the prior written

consent of Biblica US, Inc.