Trusting God's Goodness (Habakkuk)

Stephen Terry

Commentary for the May 25, 2013

Sabbath School Lesson

What if there are fifty righteous

people in the city? Will you really sweep it away and not spare the place for

the sake of the fifty righteous people in it? Far be it from you to do such a thing—to kill

the righteous with the wicked, treating the righteous and the wicked alike. Far

be it from you! Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?”

What if there are fifty righteous

people in the city? Will you really sweep it away and not spare the place for

the sake of the fifty righteous people in it? Far be it from you to do such a thing—to kill

the righteous with the wicked, treating the righteous and the wicked alike. Far

be it from you! Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?”

The Lord said, “If I

find fifty righteous people in the city of Sodom, I will spare the whole place

for their sake.”

Then he said, “May the

Lord not be angry, but let me speak just once more. What if only ten can be

found there?”

He answered, “For the

sake of ten, I will not destroy it.”

Genesis 18:24-26,

32 NIV

The book of

Habakkuk is problematic for the modern reader. We easily identify with the

author and his concerns about injustice. It is a problem today as it was back

in the middle of the 1st millennium B.C.. But how God deals with injustice

in this book is just as shocking to us as it was to Habakkuk.

The Bible

contains several earlier stories regarding God’s methods for dealing with widespread

evil. The first, the Noachian flood has God directly eliminating almost the entire

human race along with most of the animals.[i]

This goes beyond genocide but we are somehow able to accept a pure God not tolerating

evil humanity. They crossed the line and needed to be punished. After all, we

do this with our own children. Granted, we don’t drown our children for their

transgressions, but then we are not God. In His compassion God determined to

save eight righteous people, Noah and his three sons along with all of their

wives, these being the only ones who were faithful on all the earth.

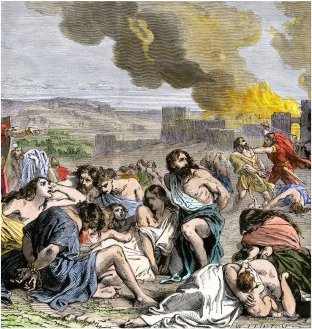

This theme

is repeated again in the story of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.[ii]

Once again all are destroyed, save Abraham’s nephew Lot and his two daughters. This

story is slightly more morally ambiguous as Lot’s caviling and incest make us a

little uncomfortable with the level of his righteousness. One gets the feeling

that although he was saved, it was more because of his relationship with

Abraham than because of any innate goodness on his part. One interesting

parallel between these two stories speaks perhaps to the compassion of God. In

both instances, destruction did not occur until the number of the righteous

dropped below ten.

Of course,

we have the later understanding of King David in the Psalms that no one is

righteous,[iii]

a sentiment echoed in Paul’s epistle to the Romans.[iv]

While this supports the concept of a universal need for grace, it does not seem

to be the perspective in Genesis. Some might see these Genesis accounts as portraying

an entirely different God than the God of the New Testament. Others might

simply see a progression in how we understand God’s character. In any event, it

appears that for the Genesis account, the author believed that one could escape

condemnation by achieving a certain level of righteousness. In Noah’s case, he

appeared to achieve it through obedience. In Lot’s, he demonstrated hospitality

to strangers.

One can

sense some of this same thinking when later the Israelites conquered Canaan. In

the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and on through much of the royal records of

Kings and Chronicles, we find the Israelites smiting their enemies and justifying

it because on a scale of one to ten for righteousness, the Israelites are ten

and the Canaanites are a one. Of course these number values get a little murky

when we consider Achan’s greedy sin,[v]

Samson’s promiscuity,[vi]

Saul’s disobedience,[vii]

and David’s adultery.[viii]

Nonetheless, the Israelites considered their tattered righteousness was still

better than that of the surrounding nations. With an exceptionalism founded in

monotheism they were able to moderate the problematic parts of these incidents in

such a way that they bolstered rather than diminished their status as a “chosen”

people.

While Achan’s

sin was speedily and dramatically dealt with by the people, one senses a

growing toleration for these behaviors over time. This, of course, brings us to

the time of Habakkuk. The lack of righteousness was reaching a point where it

was impossible to ignore. Perhaps the prophet expected a dramatic act of God

like in Noah’s or Lot’s days—a feat of righteous indignation. Instead, it is as

though God says, “I am going to use the gangs of East Los Angeles to wipe out

the Hollywood Hills because Hollywood has become so evil.” Those in Hollywood

would probably seriously question whether or not those gangs had any right to

do so as they could hardly be any better. Therefore, why wipe out Hollywood

instead of East L.A.?

This is what

Habakkuk could not understand when God told him that the Chaldeans of the

Babylonian Empire would destroy Jerusalem. They were not the chosen people. How

could they be instruments to restore justice? Perhaps, in spite of all the evil

around him, the prophet could still not see that the scales of relative

righteousness had changed. Since God did not destroy the world with a flood nor

Sodom and Gomorrah with fire until there were fewer than ten righteous people

left, maybe things had gotten that bad in Jerusalem. He had previously

demonstrated His great patience and compassion. If he continued to do so,

perhaps it would get to a point that no one righteous would remain. Perhaps

this is what Luke the Apostle was alluding to when he

questioned whether there would be any faithful left on the earth at the

Parousia.[ix]

Perhaps the second coming is not triggered so much by the spread of the gospel

as by the level of evil.[x]

When we

consider these things and how patient and compassionate God has shown Himself

to be, we might ask ourselves how few saints there may be praying for our

cities and nations and staving off destruction. This is what the prophet was

doing. The book of Habakkuk is not so much a prophecy directed toward Jerusalem

as it is a prayer directed to God. Prayer is powerful and God responds. He

guided Noah to save a remnant from the flood. He responded to Abraham’s

prayerful request regarding Sodom and saved Lot and his daughters. Even blind

Samson, with all his faults, prayed and found vengeance on his enemies when God

answered him.

This happens

in spite of what Genesis tells us about our own righteousness being efficacious

for our salvation. Several examples in the Old Testament show that we are saved

by the grace of a compassionate God. Nineveh, an Assyrian city dedicated to the

worship of Ishtar was saved by the God of Jonah. Ruth, of the Moabites, a

people who had been cursed to have no part with Israel, was saved by the God of

Naomi. Rahab of Jericho, a Canaanite, a people to be utterly destroyed by

Israel, was spared by the God of Joshua.

The lesson

to be garnered from this is that no matter how wicked your city or nation has

become, God’s grace is still powerful to save those whose hearts are His. We

should pray for the cities and countries where we live, because those prayers

may be the difference between salvation and destruction for many. Even though

we may feel alone as we struggle for justice and fairness, there may be Rahab’s

we do not know about, who, with us, are standing in the gap between life and

death for their city.[xi]

Like Rahab, they may not even know the God who loves them, but He knows their

hearts belong to Him.[xii]

Perhaps

Habakkuk was mistaken when he assumed that the Jews were more righteous than

the Chaldeans that God was sending to execute sentence on Jerusalem. Even

today, nationalistic exceptionalism is a common trend. Maybe we all at times tend

to look down on those from other countries as somehow being inferior to

ourselves. We may even feel ourselves a nation or denomination “chosen” as ancient

Israel did. But if we pervert justice and oppress others, how are we better

than anyone else?

We may think

it is safe to let our selfishness and greed have its way since it has done so

for so long without anything dire happening, but if we hurt others in this way,

do we know when the limits of God’s compassion will be passed? Do we even know

who the individuals are who might be saving our Sodom from destruction? Would

it matter if we did? If we knew that fewer than ten people were seeking the

righteousness of Christ in our community, would we behave differently? Perhaps

it is because we do not know who these people are and how many remain that

Jesus said of His coming, “But about that day or hour no one knows, not even

the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.”[xiii]

Maybe we are closer than we realize.