Stephen

Terry, Director

Cain and

His Legacy

Commentary

for the April 16, 2022, Sabbath School Lesson

"Adam made love to his wife

Eve, and she became pregnant and gave birth to Cain. She said, 'With the help

of the Lord I have brought forth a man.' Later she gave birth to his brother

Abel." Genesis 4:1-2

"Adam made love to his wife

Eve, and she became pregnant and gave birth to Cain. She said, 'With the help

of the Lord I have brought forth a man.' Later she gave birth to his brother

Abel." Genesis 4:1-2

For every Jew born such, they consider

themselves the children of Abraham. He is the great progenitor. Therefore,

every part of Genesis seeks to answer three questions. Who is Abraham? Where

did he come from? Why is he important? When the literalist reads this ancient

narrative, they do so with an emphasis on the minute details of the story more

than on the point. Abraham becomes lost in the details of was Creation six

twenty-four-hour days? Are the two creation accounts in the first two chapters

reconcilable? Were Adam and Eve real people or simply heroic metaphors? And

what about Cain, Abel, and Seth? The various cultures of humanity all claim founding

in heroic myths that resonate with the biblical narrative. We are not left

clueless about this.

One big clue is the names of the

characters in Genesis. Prior to the sojourn in Egypt, a Hebrew character's name

reflects his or her personality and role in the story. With the Exodus, that no

longer seems to be significant beyond showing allegiance to deity. For instance,

Adam means "man," fitting for the first man. Similarly, Eve refers to her role

as mother. Translated more accurately they would simply be called First Man and

First Mother, not proper names as we understand them but descriptors. Who they were

and whether they had proper names is less important than being foundations for

the heroic narrative that allows Abraham to be traced back to God.

Cain, Abel, and Seth are

likewise descriptors: Cain, "the man God gave me," Abel, "the perished one,"

and Seth, "the replacement." Abel gives us a larger clue than the rest. Why

would someone be identified as a "perished one" at birth? If constructing a

literal genealogy, this makes no sense, but if building a heroic narrative, it

makes perfect sense and illustrates why Abraham has the struggles he does.

There is a mighty battle being waged over eons involving the heavens and the

earth. But before we look deeper at Abraham in later lessons this quarter, let

us consider other clues.

The fantastically long ages of

the various characters is something we might expect in

heroic legends. Without explanation, those ages rapidly decline in length after

the flood account. It might be argued by apologists that this is because humanity

began eating meat as evidenced by the Noahic Covenant. But that idea seems

inconsistent with Abel offering a lamb from his flock in sacrifice. The author(s?)

of Genesis attempted to read back into the story of Noah the Levitical laws relating

to animals who are unclean and those who are clean. If this is the case, why

would the rules regarding how to do sacrifices also not apply which required

the one offering to eat a portion of the sacrifice? Likely, the fact that they

were raising sheep and offering animal sacrifices indicates that meat eating

was not novel after the Flood. The covenant simply recognized that reality and

was a facile transition from the apparent veganism of the Creation account and

the reality of the dietary practices of the author in his time.

Another clue to the metaphorical

aspects of the antediluvian story is the account about the sons of God and the

daughters of men becoming intimate and having offspring. One possibility that

apologists like to offer is that the sons of God are those descended from Seth

and the daughters of men are those descended from Cain. Literalism tends to

walk us into such explanations, explanations that fall apart when they fail to

explain what took place. It does not explain why the children of such unions

would become legendary heroes. On the other hand, this would be understandable

if the sons of God were angelic beings uniting with human beings and producing

children. In the understanding of many cultures, such individuals would be

demigods like Hercules or Theseus. There may be a case for the panoply of the

gods of polytheism being populated with angels cast to this earth and forced to

eke out what they could in power and control over humanity, in the process

becoming humanized themselves, to the detriment of both. This could go a long

way toward explaining how the various polytheistic cultures arose. Some would

rebut this by stating that angels are incapable of having intimate relations at

all, much less with humanity. There is no biblical basis for this belief as the

biblical canon is silent regarding sexual intimacy for angels. But understanding

how the canon came about, we know those books that were silent on the matter

were included and those that spoke about it were excluded, books like Enoch and

the Book of Giants, books considered apocryphal by the post-Nicene church.

The Book of Enoch and the Book

of Giants purport to recount antediluvian experiences. Therefore, if we examine

the biblical account metaphorically, we may place these in that same

metaphorical milieu. The Book of Giants fleshes things out further, indicating

that the fallen angels engaged in bestiality with all of Creation and produced

horrendous monsters as a result. Those inclined to take such accounts literally will doubtless find justification for monsters

such as antediluvian dinosaurs. This is something already claimed based on an

obscure quote from Ellen White in "Spiritual Gifts" about miscegenation of man

and beast. But the geological record with numerous recovered fossils tell us that by this point literalism may be getting

threadbare.

However we want to populate the world prior to the flood,

those details are only important to the literalist. Metaphorically, it is only important

to understand that everything had gone seriously wrong. Like a flawed drawing

on an Etch-a-Sketch, it might be easier to turn the whole thing upside down and

begin again, hopefully with a better result.

It may be easy to relegate this

story to the mythical mists of an ancient past with little relevance for today.

But it is a metaphor that has been lived out across many

cultures and therefore calls out a warning to the wary like blind Tiresias. As

we look around us today, we see much to be concerned about and that warning

rings ever louder in our ears. The power of metaphor is in its applicability across

cultures and time. Every time we read of the fall of Jerusalem; we see the potential

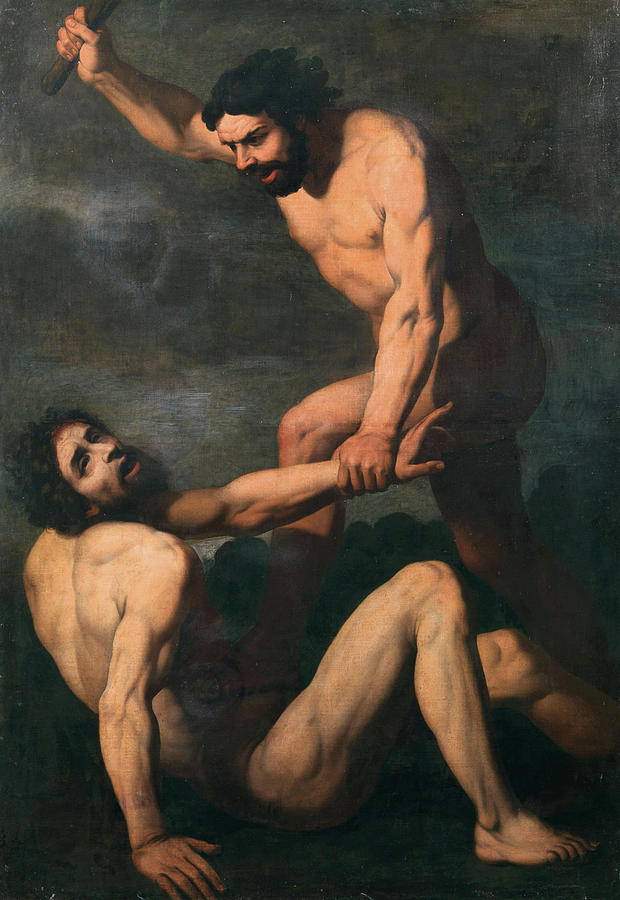

collapse of our own societies. We see in every brutal act perpetrated by one

against another echoes of the destruction of Abel by

his brother. We see in the immorality and heartlessness that surrounds us the ruthlessly

evil imaginations and acts of those in the antediluvian world, and we shudder.

But the point of the metaphor is

not to leave us in hopeless dread, demanding why doesn't God fix things? Is he

indifferent to suffering? Is he powerless to intervene? But as the story

continues, we discover that God does intervene in suffering. But how does that

explain the ongoing suffering we all experience? If he put an end to their

suffering, why doesn't he do so now? As Christians we struggle with this more

than we should. Buddhists see suffering as a part of the path to enlightenment.

If so, it is a hard lesson to learn as we keep on stumbling along the way. For

instance, one would think after God dealt with evil in the antediluvian world,

humanity would do better. But problems began almost immediately after. Sadly,

we have no problem inflicting suffering on others to "teach them a lesson." But

when we suffer, we do not see it as a lesson. Rather than learn from it, we lay

the responsibility on God and blame his indifference, impotence, or even his

existence.

As we go through Genesis this

quarter, we can search for the most righteous character in the book, other than

God. When we pick out who we think meets that definition, we can ask ourselves

whether their character is the result of the role of suffering in their life

and whether it invalidates or substantiates their faith in God. Then, once we

have done that, we can ask how their experience compares to ours. Great

literature uses metaphor to bring us to a deeper understanding of ourselves and

whom we aspire to be. The Bible does that in spades.

Many years ago, I bought a dot matrix

printer that I planned to print out Bible quizzes on. It seemed simple enough

to set up, but try as I might, I could not get the computer to communicate with

the printer. The printer cable was attached to the parallel port, and the printer

was turned on, but I kept getting the message "Printer not found!" But it was

right there plugged into the correct port. Seeing my frustration, my wife asked,

"Did you read the manual?" Like others, I had assumed I could do such a simple

task and had discarded the manual with the packing materials. Retrieving it, I

walked through the steps it gave and everything was soon working properly.

Sometimes God is like my wife was. When struggling with the problem of suffering

and getting frustrated with it, he asks me "Did you read the manual?"