Stephen

Terry, Director

Joseph,

Prince of Egypt

Commentary

for the June 18, 2022, Sabbath School Lesson

"God sent me before you to

preserve for you a remnant in the earth, and to keep you alive by a great

deliverance. Now, therefore, it was not you who sent me here, but God; and He

has made me a father to Pharaoh and lord of all his household and ruler over

all the land of Egypt." Genesis 45:7-8, NIV

"God sent me before you to

preserve for you a remnant in the earth, and to keep you alive by a great

deliverance. Now, therefore, it was not you who sent me here, but God; and He

has made me a father to Pharaoh and lord of all his household and ruler over

all the land of Egypt." Genesis 45:7-8, NIV

Last week, we discussed Joseph's

being sold as a slave to Potiphar, an Egyptian. This week, we will look at the timelines

involved with his enslavement, the captivity of the Israelites in Egypt, and

the Exodus. This will be only a shortened synopsis of much more detailed material

found at the website of the Associates for Biblical Research.[i]

While doing this, we must remember that the Bible is an Iron Age document

attempting to relate stories from the Middle Bronze Age that occurred

approximately half a millennium before the Bonze Age Collapse of the 12th

century BCE that destroyed several Bronze Age civilizations, leveling great cities

to dust and ashes. Many written archives maintained in conjunction with the

needs of powerful rulers were lost in the rubble during the dark ages following

this collapse, many not recovered until beginning in the 19th

century CE, over three thousand years later. The document that came to be known

as Genesis was an attempt to reconstruct what had been lost in the

conflagration. As a result, anachronisms occurred. For instance, several

references to camels are likely Iron Age embellishments since camels were

widely used for trade in the Iron Age but not in the Bronze Age.[ii]

The writer(s) of Genesis are not

the only ones who bring anachronisms to the biblical narrative, however. When trying

to fit Joseph's sojourn in Egypt into the chronological record of the pharaohs,

some, today, have jumped at the chance to patch him into the Hyksos period to

explain how a foreigner could rise to be second only to Pharaoh in Egypt. The

name "Hyksos" is Egyptian for "foreigners" referring to rulers in Egypt who

were probably Canaanite. But they did not rule over all of Egypt, ruling from Avaris

only over Northern Egypt. Competing Egyptian rulers reigned over the South,

also called the Upper Nile. The Hyksos ruled during the Second Intermediate Period

between the 12th and 13th Dynasties, 1782-1570 BCE. Also,

while some may have thought that the Hyksos were the Sea Peoples fought against

by the Egyptians during the time of the Bronze Age Collapse, the chronology is

off by over four hundred years.

If we take literally the Iron

Age chronology that dates the Exodus at 480 years before King Solomon's 4th

regnal year,[iii] widely accepted as 966

BCE, we end up with 1446 BCE. This places the Exodus after the Hyksos Intermediate

Kingdom which seems to fit with the idea that a pharaoh arose who didn't know

Joseph, except for one problem. In Exodus, we are told that Jacob came to live

in Egypt 430 years before the Exodus.[iv]

This puts the beginning of Israel in Egypt at 1876 BCE, a century before the Hyksos

came to power. Admittedly, this later date may be called into question because it

is reaching beyond the gap of the Bronze Age Collapse, but there is other

supporting evidence. For instance, Joseph was given as a wife Asenath, daughter

of Potipherah, the priest of On. This may simply be a literary twist of irony

involving the names Potiphar, who brought about Joseph's downfall at his wife's

insistence, and Potipherah, who blessed him with a wife, who bore him Ephraim

and Manasseh. The Egyptians of the Middle Kingdom considered On to be the chief

deity, whereas the Hyksos elevated Set, the Egyptian equivalent to Baal, a

Canaanite deity, to that position. It would seem then that to reward the second

ruler in the Kingdom, a Hyksos pharaoh would have been said to have given a

daughter of the high priest of Set, not On. An interesting side note is that

Asenath means "one who belongs to Neith." Neith was the Egyptian creator goddess

of everything.

Another evidentiary point. The

Hyksos, being from Canaan, would have been unconcerned about facial hair, but

when Joseph was brought to Pharaoh from prison, we are told he shaved.[v]

Egyptians would have been offended about a hirsute Joseph. The Hyksos? Probably

not.

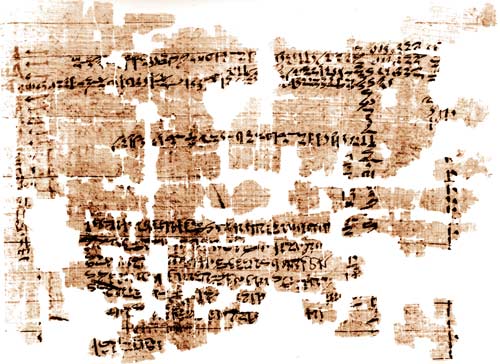

Yet another point, slave trading

was common in the time of the Middle Kingdom as evidenced by the Hieratic

Papyrus, a picture of which accompanies this commentary. The document lists the

names of ninety-five slaves, a third of which are non-Egyptian and among those foreign

names are several names like names found in the Old Testament.

Not only do these various facts

argue for Joseph's arrival in Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and specifically

for the time of Pharaoh Sesostris III who overcame the power of the local

nobility and truly became Pharaoh over all Egypt, including Nubia which he

conquered during his tenure.

Apart from the chronological

issues, other parts of the Genesis account have details that appear accurate.

For instance, if we look at the Old Testament punishment for crimes, virtually

all crimes are capital crimes that result in either death or maiming in some

way. However, The Egyptian Middle Kingdom had a prison system. We don't know how

the sentences were set, but the prison had an overseer, and Joseph, with his experience

as Potiphar's steward had two things that made him valuable to the overseer.

The prison needed to keep accurate records, and Joseph was literate. Second, he

was well acquainted with the process of caring for the physical needs of

others. Thus, he was promoted to assist the overseer.[vi]

Eventually released from prison

by Pharaoh, He came to occupy the same position for Pharaoh he had for the

prison overseer, and for Potiphar, steward over all they had. Because of his

honesty and faithfulness, Jacob trusted him more than his brothers and he was

given responsibilities commensurate with that trust. Then he earned the same

trust of the Egyptian who had bought him to be a slave and was given responsibility

second only to Potiphar's over his household. Then, thrown in prison, he again

demonstrated honesty and faithfulness so that the prison overseer placed him in

charge of everything, second only to the overseer. Finally with Pharaoh, he displayed

the same traits as well as an understanding of how to prepare for the foretold drought

that could devastate Egypt. Therefore, he reached the culmination that his

entire life was preparing him for. He became responsible for all of Egypt,

second only to Pharaoh. A household steward in

that time was expected to not only manage the household, but also needed to

oversee field workers, so this would have given Joseph needed experience with

crop growing and storage, both valuable skills to assist Pharaoh.

Was this a true story or a

parable about faithfulness and duty? As we have seen, it has elements that fit

chronologically and seem to harmonize with how things were done in the Middle

Kingdom. It has a mythological basis when we consider the circular, ascending

path of responsibility that the hero takes, each time overcoming adversity and

receiving ever more important responsibilities. This is the more important moral

of this narrative, that honesty, faithfulness and trust will prevail in the

end. So much of what we are told by the world is that you get ahead by knocking

someone else down. In the story of Joseph that never happens. It presents us

with something we don't often experience. The faithful, honest, and trustworthy

employee does not get the promotion. Instead, it goes to the sycophant or the

relative. Does this mean the story makes a good children's story but nothing

more?

It may be problematic and appear

to be more of a fairy tale because it is another "happily-ever-after" story.

Like the book of Job, who despite great suffering ends up richer and better off

than before. But the prophet Habakkuk knew that was not the case.[vii]

He saw so much injustice, he asked God why he allowed it? Why is there no happy

ending for so many? The reality is that we live in a wicked world where things

do not end happily ever after. Isaiah, the prophet whom Jesus liked to quote,

was sawn in two by wicked King Manasseh. John the Baptist who faithfully heralded

Christ's ministry was beheaded by evil King Herod. Even Paul, who did more to

establish the Christian church than any other apostle was also beheaded at the

command of a dissolute emperor.

The moral here is not about

happy endings, but about the value of honesty and faithfulness to us as their

own rewards. When we fail to appreciate that, the results may load us with

guilt that stays with us for the rest of our lives, robbing us of sleep and

destroying our peace of mind. Joseph's brothers did not find that peace of

mind. They continued to be in fear that he would treat them as they had treated

him.[viii]

While expressed in the story in terms of material rewards, a clear conscience

and a decent night's sleep are beyond price, and that is the real lesson here.